In Solidarity with Ambai’s Short Stories

Originally published at https://www.theantonymmag.com/ on August 5, 2022

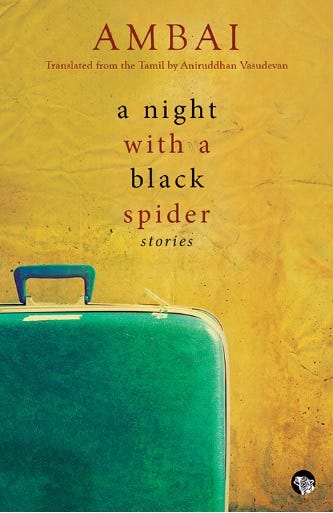

For a Bengali woman, stumbling upon a collection of contemporary Tamil short stories is uncommon, even when you are a student of literature. Ambai’s collection of short stories, bunched together under the title of A Night with a Black Spider: Stories — was gifted to me by a dear friend. When she handed me the book, she told me that it was her small gesture of offering solace to my anguished mind simply because she didn’t think that anything could soothe my open wounds apart from these stories — stories of women who have survived many ordeals.

It was much later though when I finally got around to reading it that I realized my friend’s act of gifting the book was a gesture of solidarity rooted in the shared experience of pain, a sense of togetherness wherein the feminine existence finds a collective voice across the boundaries of caste, class, ethnicity, and generations.

The pandemic was still looming large. Incidents of abuse, trauma, and gloom made their way into the newspapers and social media. It seemed easy to lose faith as cynical melancholia had crept into my bones — and a writer of a faraway state, a faraway language, and a faraway culture suddenly pushed open unforeseen dimensions to the lost meanings of solidarity and love!

In the Introduction of the book, Ambai writes, “It is in the constant struggle to know which is story, which is life, where does story end and life begin, where does life end and story begin, that writing happens. It is definitely a happening.”

All of these stories reflect upon such happenings, they make the readers aware of the unexpectedness of life and its absence, death — a range of emotional, political, and cultural tensions lie between these two forces. Ambai lists them as, “desire, loss, financial security, penury, friendship, loneliness, exhaustion, enthusiasm, disappointment, happiness, lust, detachment.”

Ambai’s fiction is rooted in the post-colonial literary tradition of the ‘Indian short story’ — a genre that proliferated in the early 20th century, especially after the 1930s with the Progressive Writer’s Movement in India. It designated the central function of literature to be the means of documenting the repository of the “tensions and pulls” that lie at the bosom of the experiences of marginalized identities in the pluralistic society of independent India. Emerging from such a tradition, her short stories draw the narrative lens to the quotidian lives of these marginalized identities, whether they be low-caste, low-class, or the low-gender, women.

Placed within the intensifying struggles of power in the post-colonial Indian society, the stories in this collection offer a site of resistance — a site where the oppressed identities contest their claims and assert their everyday living against the forces that discriminate against them, and thus arises the aforementioned solidarity. Ambai’s short stories not only amplify the narratives of different women within the shackles of patriarchy but also establish that these narratives are as much representative of the voices of women as it is of other oppressed identities such as Dalits and lower classes. In fact, these stories are strangely clairvoyant of an intersectional politics of feminism wherein oppression (and likewise, solidarity) becomes multidimensional, interspersed with overlapping hierarchies of caste, class, ethnicity, age, and gender.

Ambai sets the stage with the retelling of the popular myth of Asura Mahishan and the Devi, albeit as it is narrated in Tamil classical literature. The premise of this popular myth entails Mahishan being killed by the Devi. But she introduces an anomaly in her interpretive narrative in the story titled A Love Story with a Sad Ending where Mahishan falls in love with the beautiful Devi. His doomed love results in his death, filled with longing, lust, and separation from his beloved. Mahishan is paralleled with the lowly and ugly beings of the netherworld (a reference to the low-born of an inferior caste) and the Devi as a symbol of power and beauty from the upper stratus, the Gods. In doing so, Ambai takes the age-old myth of the battle between gods and demons and places it carefully amid the contemporary realities of segregation and untouchability that is historically visible in India. This story is a reflection of the Dravidian narrative where the Asuras and the demons have often been equated with the dark-skinned natives of the region, contesting the superiority of the Aryans.

At this point, it is important to note how the limited space of the short story evokes such strong emotions, even in the minds of readers who are not familiar with the symbolisms replete with varied cultural and literary connotations. Such resplendent cultural and literary connotations are found in all the stories in the collection — sometimes as ragas and songs, sometimes as food and flavors, sometimes as references to ancient writers, sometimes as practices and rituals — but they are always aesthetically placed to pique the interest of readers across the world.

Perhaps, the task of the translator, Aniruddhan Vasudevan, also needs to be acknowledged here because he makes sure that these imageries, allegories, and allusions are aptly transplanted into the heart of readers from other cultures. He uses the italicized roman alphabet to denote the poetry, songs, and untranslatable terms as pronounced in Tamil while also providing English translations of the same, side by side. In doing so, the musicality of the Tamil language is not lost yet the readers do not find it difficult to decipher the meanings, without having to refer to footnotes that disrupt the experience of reading. As a reader who is not familiar with Tamil, that is the extent of my comments on the translation because I have no means to assess its faithfulness to the language of origin.

Moreover, these stories travel to different cities, regions, and cultures across the world but they stick to Tamil women as protagonists or the narrator. The experiences of these Tamil protagonists and narrators explore interactions and conversations with varying cultures and the strains that arise out of the multiculturalism of the globalized world.

Multiple stories titled Journey, followed by a number, form the interludes between the stories. This collection contains Journey 11 till Journey 17, and then it ends with Journey 20; Journey 18 and Journey 19 remain missing. These journeys, by train or bus or autorickshaws, make the readers familiar with the different facets of human nature as they tell stories of travel to big cities, to foreign lands, and to fascinating people.

Journey 11 follows a young woman to her hometown where she discovers how her aging father is battling with the fear of the changing times and the inevitability of death as he deals with the grief and bereavement of losing his dear ones in his senile years.

The magnanimous act of a child who loves the sea manifests hope and happiness buried in a single moment in Journey 13 which takes place inside a bus. The integral intermingling of water and caste is brought to the fore in Journey 14. Journey 17 travels to the metropolitan city, Delhi, highlighting the unsafe city life and the crude practicality in the inability of a woman to support another woman, despite being moved by her suffering.

All in all, these journeys bring out the flavors of solidarity in human dialogue. In the final journey, Journey 20, the agonies of a Gujarati couple after they migrate to Mumbai during the Gujarat riots of 2002 are revealed through the painful reflections of the narrator and her friend during an autorickshaw ride.

The other stories in the collection traverse the spatial and temporal shifts of constructs such as culture, politics, caste, class, gender, age, and ethnicity. Humans from across generations, classes, and castes speak to each other, conversing about differences that do not find their resolve in the rational constructs of the law. Finally, the resolution of all conflicts takes place in the aforementioned concept of feminist solidarity as the stories speak of women who are relentless and resilient, not afraid to take difficult decisions which emancipate them and lead them to the path of healing.

In the story eponymous to the title, The Night With A Black Spider, a lonely woman’s mental and bodily pain searches for commiseration with a black spider on the wall of a hotel room. While, in the story titled Saluki, a cosmopolitan Tamil writer’s discomfort is shared by an Arab pedigree dog when she visits an international writers’ conference in Chicago.

A young doctor, Tirupasundari, finds out that her experiences of devising and delivering a talk on Tamil culture to the diasporic Tamil audience in Paris are like navigating a complex maze of traditionalism and prejudices in the story titled Ravana’s Fortress. Ultimately, she finds her much longed-for solace in the crows of the foreign land.

A woman’s strained relationship with the elusive nature of time is reflected in the symbol of a statue of an ancient Tamil poet, Tiruvalluvar, which suffers weathering and erosion over the course of many years in the story titled Tiruvalluvar Under A Tree.

Burdensome Days tells the story of a talented classical musician, Bhramara, who entangles herself in a marriage with an upper-caste, upper-class, powerful man from a family of politicians. Her prolonged self-effacement in her burdened marriage is narrated through pointed descriptions of all the burdens that were shouldered on her. Distraught Bhramara finds her peace in reconnecting with her long-lost friend of youthful days, Nithila, as she finally takes the intrepid action of stepping out of her emotionally abusive marriage.

In the story titled A Moon to Devour, a woman scholar recalls an incident where she was exploited and emotionally abused by her lover, an erudite and educated young man who was a scholar and a poet. The story journeys through her trauma likening itself to the waxing and waning of the moon. Her suffering, unable to find justice within the constraints of law, flows into an act of violence that manifests as retrospective justice. Finally, she finds her solidarity with her ex-lover’s, albeit also her abuser’s, mother who becomes the dearest companion in her life.

Overall, the book reiterates feminine resilience, urging one to implore justice and equality. It makes one think: Where does justice reside? In literature, in law, in politics, or in the everyday negotiations of life? What does equality mean for the feminine, the oppressed, the subjugated, and the ones who carry the burden of history? And most importantly, where and how does solidarity reside within their narratives? These are questions that are rightfully left unanswered within the generic markers of the short story.

In a post-pandemic world where suffering, corruption, pain, and loss are rampant around us, where we all stand divided and disconnected from each other, these stories reinforce the significance of empathy. They occupy the liminal spaces between the opposing forces of life and death, of harmony and disharmony. They draw a magnifying glass at the injustices of the world, making the readers aware of the cracks and faultlines in human society but thereafter, they lead the readers to a space of solidarity with the suffering and the oppressed. They reaffirm that no matter how ruptured human existence becomes, empathy and solidarity can take us to places where all hope is not lost, where traumas find resolution, and where healing is possible!

About the Author:

Ambai is the pseudonym of Dr. C.S. Lakshmi, one of the foremost writers of Tamil fiction. Her short stories have been translated into three volumes — A Purple Sea, In A Forest, A Deer, and Fish in a Dwindling Lake. In a Forest, A Deer shared the Hutch-Crossword Award for translated fiction in 2007. Ambai has also won the Pudumaipiththan memorial lifetime achievement award for her contribution to literature from the US Tamil cultural organization Vilakku in 2005 and the Lifetime Literary Achievement Award of Tamil Literary Garden, University of Toronto, Canada, for the year 2008. In 2011, Ambai was awarded the Kalaignyar Mu. Karunanidhi Porkizi Award for fiction by the Booksellers and Publishers’ Association of South India. The University of Madras awarded her for excellence in literature during the centenary celebrations of International Women’s Day in March 2011. In 2021, she received the Sahitya Akademi Award for her short stories in Tamil. She has been an independent researcher in Women’s Studies for the last thirty-five years. She is currently the director of SPARROW (Sound & Picture Archives for Research on Women).